Before we get started on our topic for today, I just want to remind you that my newsletter will be going out this week, so if you would like to sign up you can find it on the sidebar to this blog.

Now, where were we. Ah yes, we left the Jane Austen Center and walked up Gay Street, an exceedingly steep hill, to the Circus. I paused here and took several pictures from all kinds of angles.

I particularly liked this one because of the sun reflecting off the windows and the gold toned stone. The circus, is a circle, and the townhouse curve around it in the most elegant way, broken only by the roads.

The next picture shows the top of the circle and the island of green in the center and after that the matching wing to the first picture completes the circle and you get a little glimpse of mother patiently waiting for the photographer to finish.

The Circus, originally called King's Circus, was designed by the architect John Wood the Elder, who died less than three months after the first stone was laid. His son, John Wood the Younger completed the scheme to his father's design between 1755 and 1766.

Wood's inspiration was the Roman Colosseum, but whereas the Colosseum was designed to be seen from the outside, the Circus faces inwardly. Three classical Orders, (Greek Doric, Roman/Composite and Corinthian) are used, one above the other, in the elegant curved facades. The frieze of the Doric entablature is decorated with alternating triglyphs and 525 pictorial emblems, including serpents, nautical symbols, devices representing the arts and sciences, and masonic symbols. The parapet is adorned with stone acorn finials. When viewed from the air the Circus along with Queens Square and the adjoining Gay Street form a key shape which is a masonic symbol.

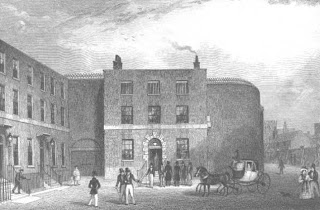

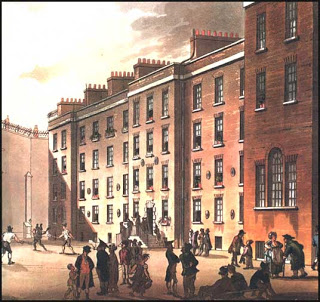

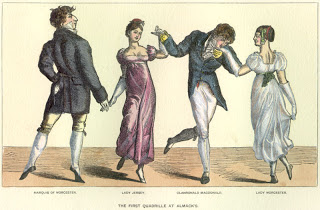

The central area was originally paved with stone setts, covering a reservoir in the centre which supplied water to the houses. In 1800 the Circus residents enclosed the central part of the open space as a garden. Now, the central area is grassed over and is home to a group of venerable plane trees planted in the 1820's, so they could well a have been there at the end of the Regency. You can see those plane trees in my first picture. Here are a couple of views of the Circus, from 1773 and 1829 respectively. You can clearly see the open piazza in the first one.

Among the lessees of the south western segment, which was completed first, were the eminent politician William Pitt and his cousin Lady Lucy Stanhope, who took adjoining plots. On 18 November Lady Stanhope moved into her new-built house - the first in the Circus to be inhabited. Pitt's house was reported to be almost fit for his reception and he arrived in Bath around Christmas time. The most desirable houses were those on the north side, with their sunny south-facing fronts. William Pitt, by then Earl of Chatham and in his second term as Prime Minister, moved from his double-sized house in the south-western segment to one almost as large at no.11, while the spacious central house at no.14 was taken by John, 4th Duke of Bedford. The close proximity was convenient in October 1766 as Chatham and Bedford pounded between each other's houses in a round of political bargaining. For men such as these the Circus provided a second or third home. They were seasonal visitors, part of the ebb and flow of the haute monde between London, country estates and Bath. Permanent residents included those who catered to the seasonal flow, such as the artist Thomas Gainsborough at no. 17 and his sister Mary Gibbon, who became the chief lodging-house keeper in the Circus, running three houses there.

While small, this image gives an overview of the Circus, originally called King's circus by the way. You can see how each of the three roads intering the Circus are all confronted by a grand arc of building, just like the one in my picture of the north section.

This is an end of one of the crescents, you clearly see the columns, the acorns at the edge of the roof and the style of each town house, not to mention the blocked in windows, likely filled in to avoid paying window tax.

This last is typical me, a peek over the wrought iron railings, which would have been painted green or blue in Georgian times, into the area. The floor below street level, which usually contained the kitchen and cellars where the servants worked. Accessed by outside steps, tradesmen would have delivered through door from the street. Sometime there was a manhole in the street down which the coalman would deliver coal.

Well, there is lots more to show you about Bath, but I think this is enough for today. Until next time: Happy Rambles.