The last day of February and I have to finish edits for a book due out in the Fall. If you like sneek peeks, how about this title. Lady Rosabella's Ruse.

Oh and I have my UK cover for More than a Mistress . Here it is here. It will be out in North America in May.

. Here it is here. It will be out in North America in May.

London

My next topic is something I have blogged about before. The Thames River Police I . Thames River Police II

I have linked to the earlier posts so you can take a look at them as an introduction. This time, I was able to visit the museum and can fill in a few more details. I must say I liked the idea of standing in a building that parts of it dated back to the Regency. And it is nice to know that the Force continues to this day, albeit in a very different form.

The pictures I am adding today were taken in the museum with the kind permission of the museum's curator Robert Jeffries, who was a member of that illustrious Police force.

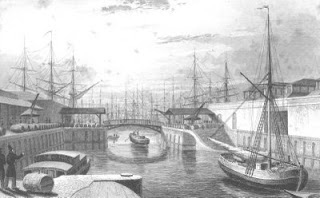

This picture is from 1859, but still it gives the feel of our time, the spars and masts, the wooden boats beached on the side of the river, the building unchanged from that above.

This picture is from 1859, but still it gives the feel of our time, the spars and masts, the wooden boats beached on the side of the river, the building unchanged from that above.

The Museum contains many treasures and mementos from the work of the police, as you can see from this cabinet.

Of particular interest is the police boat gun from 1798.

Of particular interest is the police boat gun from 1798.

You can make out the stock behind the glass and the thole, a wooden pin or one of a pair, set upright in the gunwales of a rowing boat to serve as a fulcrum in rowing (rowlock), only in this case it was used to support this very large weapon. It was too large to be held and fired.

Publicans at inn like the Town of Ramsgate, pictured in detail last time, and the Prospect of Whitby, pictured here, were owned by what were known in those days as Master Lumpers. They organized the Lumpers, the men who unloaded the ships. they were also the men who stole a great deal of the contents of those ships, seeing it as a gratuity for the work they did. Everything from sugar to coal.

Some of the terminology for the Thames River Police and those working on the river at the time:

Watermen - constables

Surveyors - warrant or customs warrant.

Lighters - boats wich take the cargo off to unload it a the warehouses

Lumpers - the labourers who unloaded the cargo

Sweepings - the first mate on a sugar carrying ship had the rights to "sweepings" what was left on the deck after unloading, and he would sell these rights to anyone who wanted to do the work to sweep them up. Interesting to think about what might have been in the resulting bag of sugar. or not.

Spillage - anything spilled was seen as a perk for various individuals and somehow there was a lot of spillage.

Tipstaff - a badge of office, like a warrant card today, and sometime used to carry a warrant for arrest in the handle. Also a weapon, a forerunner of the truncheon.

This is an inspectors tipstaff from 1827. And here are a couple of early handcuffs.

This is an inspectors tipstaff from 1827. And here are a couple of early handcuffs.

Note the policeman's rattle in the second picture. The l-shaped large wooden object.

Rattles came into use sometime in the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century when night watchmen and/or village constables used them to "raise the alarm". They proved an ideal method to summon aid, sound the fire alarm, or, just generally get folks attention. A traditional rattle was constructed of wood, usually oak, where one or two blades are held in a frame and a ratchet turned - by swinging - to make the blades `snap' thus creating a very loud noise.

Of course we have only touched on the surface of the river and its police force but I do hope you have enjoyed the visit.

Until next time, Happy Rambles

Oh and I have my UK cover for More than a Mistress

London

My next topic is something I have blogged about before. The Thames River Police I . Thames River Police II

I have linked to the earlier posts so you can take a look at them as an introduction. This time, I was able to visit the museum and can fill in a few more details. I must say I liked the idea of standing in a building that parts of it dated back to the Regency. And it is nice to know that the Force continues to this day, albeit in a very different form.

The pictures I am adding today were taken in the museum with the kind permission of the museum's curator Robert Jeffries, who was a member of that illustrious Police force.

This picture is from 1859, but still it gives the feel of our time, the spars and masts, the wooden boats beached on the side of the river, the building unchanged from that above.

This picture is from 1859, but still it gives the feel of our time, the spars and masts, the wooden boats beached on the side of the river, the building unchanged from that above. The Museum contains many treasures and mementos from the work of the police, as you can see from this cabinet.

Of particular interest is the police boat gun from 1798.

Of particular interest is the police boat gun from 1798. You can make out the stock behind the glass and the thole, a wooden pin or one of a pair, set upright in the gunwales of a rowing boat to serve as a fulcrum in rowing (rowlock), only in this case it was used to support this very large weapon. It was too large to be held and fired.

Publicans at inn like the Town of Ramsgate, pictured in detail last time, and the Prospect of Whitby, pictured here, were owned by what were known in those days as Master Lumpers. They organized the Lumpers, the men who unloaded the ships. they were also the men who stole a great deal of the contents of those ships, seeing it as a gratuity for the work they did. Everything from sugar to coal.

Some of the terminology for the Thames River Police and those working on the river at the time:

Watermen - constables

Surveyors - warrant or customs warrant.

Lighters - boats wich take the cargo off to unload it a the warehouses

Lumpers - the labourers who unloaded the cargo

Sweepings - the first mate on a sugar carrying ship had the rights to "sweepings" what was left on the deck after unloading, and he would sell these rights to anyone who wanted to do the work to sweep them up. Interesting to think about what might have been in the resulting bag of sugar. or not.

Spillage - anything spilled was seen as a perk for various individuals and somehow there was a lot of spillage.

Tipstaff - a badge of office, like a warrant card today, and sometime used to carry a warrant for arrest in the handle. Also a weapon, a forerunner of the truncheon.

This is an inspectors tipstaff from 1827. And here are a couple of early handcuffs.

This is an inspectors tipstaff from 1827. And here are a couple of early handcuffs.Note the policeman's rattle in the second picture. The l-shaped large wooden object.

Rattles came into use sometime in the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century when night watchmen and/or village constables used them to "raise the alarm". They proved an ideal method to summon aid, sound the fire alarm, or, just generally get folks attention. A traditional rattle was constructed of wood, usually oak, where one or two blades are held in a frame and a ratchet turned - by swinging - to make the blades `snap' thus creating a very loud noise.

Of course we have only touched on the surface of the river and its police force but I do hope you have enjoyed the visit.

Until next time, Happy Rambles