by Michele Ann Young

My we are flying around the world at a rapid rate!

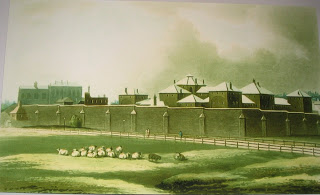

If you are anything like me, you would have found the look of Hyde Park Barracks in the earlier post distinctly depressing on the outside.

If you are anything like me, you would have found the look of Hyde Park Barracks in the earlier post distinctly depressing on the outside.

On the other hand, some of these people had been sitting in wrecks like the one pictured here for a very long time. Perhaps four square walls didn't look quite so bad after all.

These ships were called prison hulks and they eased the overcrowding in prisons on land. And of course, conveniently located the prisoners off shore or in the Thames estuary for when it was their turn to be transported. sometimes they remained on board for years.

One can imagine that it would be dark and dank with absolutely no privacy.

The men would be shackled during the day in ankle shackles such as these, which would be connected to another chain which encircled waist or throat.

During the day they were put to work on all sorts of projects, depending on where there ship was in relation to shore.

Many of the hulks were located near Woolwich which was expanding rapidly at the time and needed lots of labourers. With the marshes on one side and the naval docks and the Royal Arsenal on the other, escape was difficult.

My we are flying around the world at a rapid rate!

If you are anything like me, you would have found the look of Hyde Park Barracks in the earlier post distinctly depressing on the outside.

If you are anything like me, you would have found the look of Hyde Park Barracks in the earlier post distinctly depressing on the outside.On the other hand, some of these people had been sitting in wrecks like the one pictured here for a very long time. Perhaps four square walls didn't look quite so bad after all.

These ships were called prison hulks and they eased the overcrowding in prisons on land. And of course, conveniently located the prisoners off shore or in the Thames estuary for when it was their turn to be transported. sometimes they remained on board for years.

One can imagine that it would be dark and dank with absolutely no privacy.

The men would be shackled during the day in ankle shackles such as these, which would be connected to another chain which encircled waist or throat.

During the day they were put to work on all sorts of projects, depending on where there ship was in relation to shore.

Many of the hulks were located near Woolwich which was expanding rapidly at the time and needed lots of labourers. With the marshes on one side and the naval docks and the Royal Arsenal on the other, escape was difficult.

James Hardy Vaux was a prisoner on the Retribution, an old Spanish vessel, at Woolwich during the early 1800s.

While waiting to be transported for a second time to New South Wales, he recalled:

Every morning, at seven o'clock, all the convicts capable of work, or, in fact, all who are capable of getting into the boats, are taken ashore to the Warren, in which the Royal Arsenal and other public buildings are situated, and there employed at various kinds of labour; some of them very fatiguing; and while so employed, each gang of sixteen or twenty men is watched and directed by a fellow called a guard.

These guards are commonly of the lowest class of human beings; wretches devoid of feeling; ignorant in the extreme, brutal by nature, and rendered tyrannical and cruel by the consciousness of the power they possess….

They invariably carry a large and ponderous stick, with which, without the smallest

provocation, they fell an unfortunate convict to the ground, and frequently repeat their blows long after the poor fellow is insensible.

The prisoners had to live on one deck in group cells that were barely high enough to let a man stand up. The officers lived in cabins in the stern. Disease such as dysentry and typhus were rife caused by the lack of fresh water, overcrowding and vermin. Many died. The men stole from each other, and their guards stole their issued clothing. Punishments were harsh, primarily the cat o' nine tails and solitary confinement.

It was also difficult for relatives to visit and bring them the necessities of life as they often did in the prisons on land.

And they still haven't started on their journey to Bontany Bay.

Until next time, Happy Rambles.