person. I do of course mean Scotch whisky (and that too is the correct spelling).

My current work in progress is set in Scotland and part of my plot revolves around a whisky distillery. There are a number of discussions about the origins of uisge beatha, water of life (uisge sounds like usky anglicized to whisky).

Most experts believe the knowledge of distilling was brought from Ireland by the Scots in the fifth century A.D., along with the Gaelic language. Scotch whisky is made from barley malt and I will not delve into the actual process here.

Most experts believe the knowledge of distilling was brought from Ireland by the Scots in the fifth century A.D., along with the Gaelic language. Scotch whisky is made from barley malt and I will not delve into the actual process here. Traditionally in the Highlands, whisky was provided before breakfast to sharpen the appetite, since it was seen as both a libation and as a health drink. It was given to infants and children too. It was offered to anyone who crossed a home’s threshold as a matter of courtesy at any time of day or night.

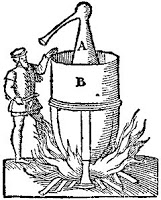

When an illegal still was found, the equipment would be smashed and the owner of the still punished – if found.

An Act of Parliament passed in 1814 prohibited any still in the Highlands with a less than 500 gallon capacity. A fantastical size for that period of time. Moreover, thereafter all whisky produced in the Highlands could only be sold in the Highlands, effectively making the legal production and selling of whisky almost impossible. Needless to say it only served to encourage illicit stills

and an increase of smuggling. In 1823 14,000 illicit stills were discovered and smashed, but many more went undiscovered.

Scotsmen with vision knew this had to change and in this year a new act was passed making 40 gallons the minimum size for a still and setting the duty at a reasonable rate. Illicit production slowly dwindled away along with smuggling.

Of course how all this fits in my story has yet to be revealed to me, but I hope you enjoy reading a small snippet from my research. It is nice to know that this ancient Scottish skill has survived to produce one of the world's most popular drams. Slàinte

This post originally appeared on the blog at eHarlequin.com, but I wanted to record it here too, since I may have other posts on this topic.

Until next time, Happy Rambles